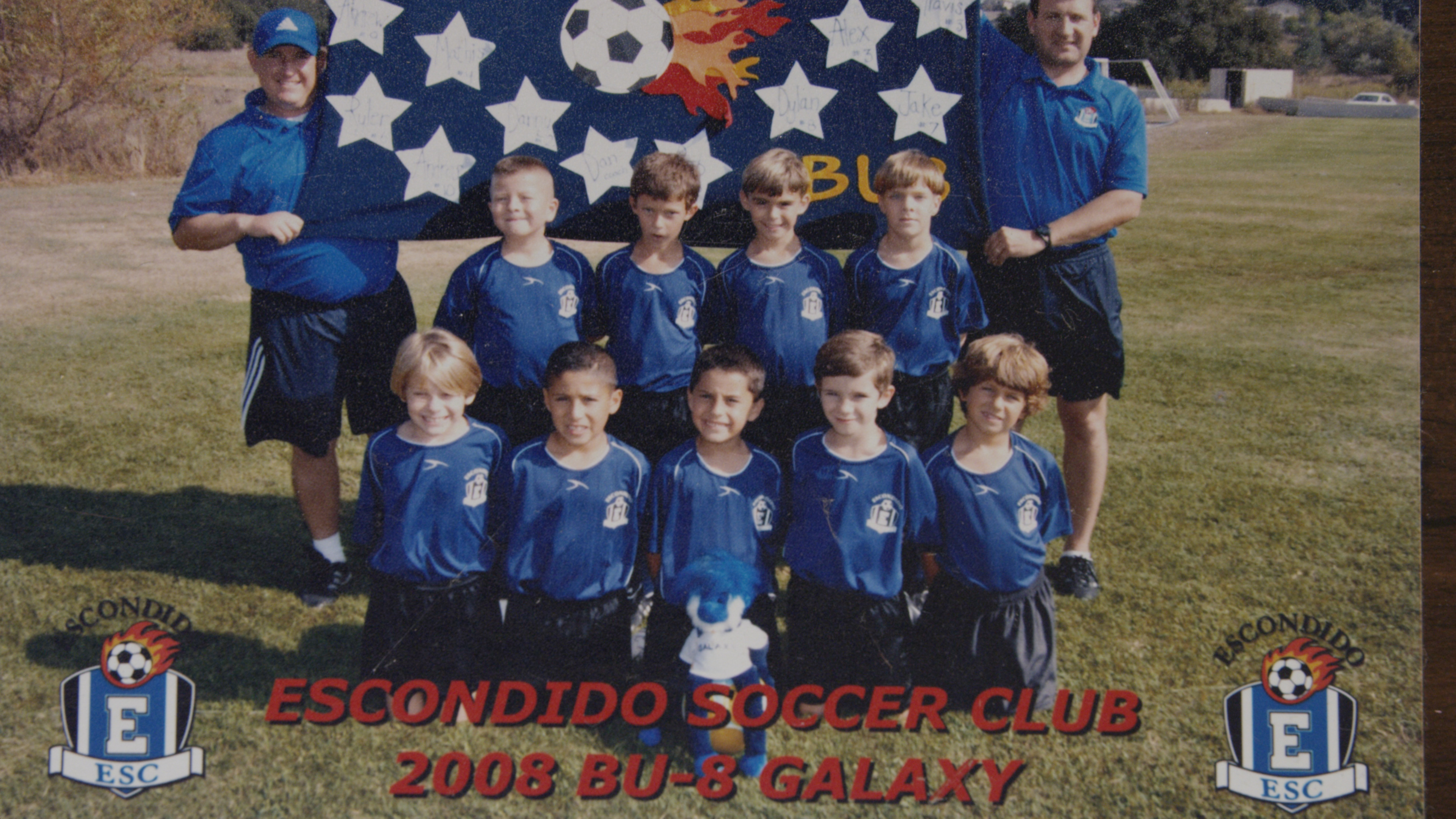

When a 14-year-old soccer player gets injured, it’s safe to assume they rolled their ankle. Or they pulled a muscle. Or worst case, they tore a knee ligament. Suffering a spinal stroke in the middle of the field? No way.

Danny Smuts of Mission Hills, San Diego, collapsed during the second half of a soccer game in 2015 at just 14 years old, and he hasn’t walked since. “I knew as soon as I fell it wasn’t an ordinary injury,” he says. And it wasn’t. He inexplicably had a T-7 level spinal stroke, which struck the bottom of his ribcage, stunting blood flow and killing nerve cells. In an instant, Danny was transformed from a star athlete feared by opponents for his speed, to a paraplegic who would never walk again.

“It was just a big question mark to me,” Danny says of the aftermath of his injury.

“How am I going to go to school?”

“How am I going to hang out with my friends?”

“Why did this happen?”

In the face of total uncertainty, Danny started his 7-week-long stint at the hospital doing physical therapy. Just two days after leaving, he attended his first day of freshman year in high school. “I wanted school to be the same way it was before the injury, but I knew it wasn’t,” he says. “It was work going anywhere. I went to school for six hours, and then came home and power nap for five hours because I was so tired from pushing around all day.”

Naturally, these radical changes took a tole, and Danny longed for his former athletic life. “There were a few darks spots,” says Danny, “where I was just really missing going out on that field and just playing with my friends, and everyone being there.”

Not only had his stroke stripped him of the sports he loved, but it had taken away the sense of community that came with them. Or so Danny thought.

The Adaptive Sports and Recreation Association in San Diego provides sports programs for adults and children with physical disabilities. It’s common for disabled individuals to feel isolated from the rest of society, as most people don’t understand what they’re going through, and our world is primarily designed for those with able-bodies. ASRA identified these issues and built an organization that would help disabled people of all ages develop skills that would transcend beyond the court or field.

When Danny first found wheelchair basketball at ASRA, he was frustrated by his own limitations. “I didn’t feel like I was as big of an impact on the game as I was before,” he says, “and so it was just a big change for me.”

But once a competitor, always a competitor, and it wasn’t like Danny to give up. His injury might have robbed him of his legs, but it hadn’t robbed him of his competitive spirit.

Like all sports, wheelchair basketball takes time and practice. But once Danny put the work in as he had with soccer and baseball, he fell in love with his new favorite sport. “Getting back to that competitive feeling of wheelchair basketball was just so fun for me,” he says. “I think that’s what I missed the most before I started playing basketball.”

Danny says wheelchair basketball can be just as intense and tactical as able-bodied sports. “There’s a lot more strategy and I feel like there’s a lot of teamwork that goes along with wheelchair basketball,” he explains. “And working as a unit really helps your team.”

Don’t think these athletes play soft just because they’re in wheelchairs. In fact, they play even tougher. “It gets intense. It gets really competitive,” says Danny. “It’s part of the game that I love the most.”

ASRA has provided Danny with much more than a competitive outlet. He’s also part of a team again.

“I fell in love with the whole community,” says Danny, and he’s made friendships and found mentors for life. “It’s definitely a family. We all know each other very well and it’s just cool to have that group of people who share that similar challenge as you do.”

Wheelchair basketball teams are incredibly diverse, since each one has players with all sorts of different physical disabilities. “There’s a big sense of personality on the team just because everyone’s different,” says Danny. “You just get a new story for every team you play against.”

The richness of this community is inspiring and life-affirming for people like Danny. “I feel like I’ve gone a long way since my injury,” he says, “through sports and just as a person in general, and just being more open to the people around me.”

Because of ASRA, Danny continues to have ambitious athletic goals and has his sights set on playing wheelchair basketball in college. Right after his injury, he never would have thought that was possible.

When Danny is on the basketball court, he knows he’s doing much more than playing a sport. “I always think of the example I’m setting for the younger kids,” he says, “that almost don’t know the future that they could have in the sport or just any sport at Adaptive Sports.”

ASRA and wheelchair basketball have given so many people like Danny hope. “There is life after injury,” he says. “It’s not the end of my old life from the injury, it’s just the beginning of a new one.”

Also published on Medium.